A journey down one of Britain’s most historic waterways, the Kennet and Avon Canal from Top Lock in Bath to the Dundas Aqueduct.

4 minute extract from BBC Four Goes Slow. Slow down the pace, sit back, relax and enjoy.

Filmed in real time to allow viewers to take in the images and sounds of the British countryside, spot wildlife and glimpse life on the towpath as if they were there. Archive stills and graphics are used to deliver salient facts about the canal and its social history.

A Brief History of the K&A Canal

The Kennet and Avon was built as the industrial highway of its day to transport coal, iron ore, tobacco and all sorts of agricultural products between towns and villages stretching all the way from Bristol in the west to Reading in the east.

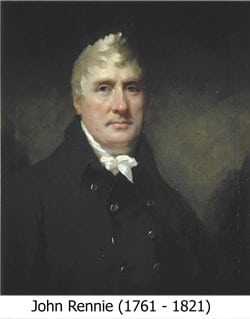

In the early part of the 18th Century the river Kennet at Reading and the River Avon at Bath were made navigable. The areas between these were crying out for a waterway link and in 1794, Scottish architect and engineer John Rennie was appointed to close the gap – which involved construction of the Caen Hill Flight of locks. As a highly respected engineer, Rennie had been responsible for building many bridges, canals and docks and was honoured, after his death, with being buried in St Paul’s Cathedral.

For the next 16 years, navvies risked their lives cutting and digging almost 60 miles of canal, built 100 locks, 2 tunnels and almost 200 bridges, viaducts and aqueducts between Bath and here at Foxhangers! A double-track iron railway on wooden sleepers linked the canal with the town of Devizes until the Caen Hill Flight of locks was completed in 1810; it was then possible to navigate from London to Bristol.

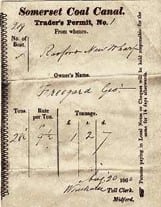

With the advent of The Kennet and Avon Canal, The Somerset Coal Canal (at one time serving 80 Somersetshire collieries) now had access – from the Dundas Aqueduct – to previously unimaginable business opportunities offered by supplying London; not to mention the more local areas of Wiltshire and Berkshire where coal supplies had, until then, been very limited. The Kennet and Avon also linked with the Wilts and Berks Canal at Semington.

Many of the stone quarry owners in Bath saw the potential of the Kennet and Avon Canal and became some of its biggest shareholders; soon their stone was seen along the length of the canal being used by various developers in many new locations (including the Foxhanger Barn and Lock Keepers Cottages for example).

1804 Cargo Lists for the Kennet and Avon Canal

EAST (towards Reading & London)

- Bath building stone Chalk

- Hanham paving stone

- Limestone from Bristol and Bath Peat

- Slate

- Tin Plate

- Iron from Wales

- Copper

- Salt

- Timber

- Fruit from the Mediterranean

West (towards Bath & Bristol)

- Gravel

- Chalk

- Flint

- Peat ash

- Timber

- Grain & flour

- Timber and pitch from the Baltic’s

- Tea from the East Indies

- Fruit from the Mediterranean

- Grain & flour

- Sugar from the West Indies

However despite high expectations, trade never achieved what had been expected and when the Great Western Railway bought the Canal in 1852 there was a deliberate policy not to invest too much in maintenance. By the end of the First World War the number of boats using the canal was in decline.

However despite high expectations, trade never achieved what had been expected and when the Great Western Railway bought the Canal in 1852 there was a deliberate policy not to invest too much in maintenance. By the end of the First World War the number of boats using the canal was in decline.

During the Second World War, a large number of concrete bunkers known as pillboxes were built as part of the line to defend against an expected German invasion, and many of these are still visible.

In 1948 navigation effectively closed and the Government planned to close the canal completely but this rallied local canal enthusiasts determined not to let that happen, and in 1962 the Kennet and Avon Trust were formed with the aim of restoring the whole waterway.

After much hard work by the Trust and its volunteers, the Queen was invited to officially re-open the Kennet and Avon Canal and this happened at the top of the Caen Hill flight of locks on 8 August 1990. Restoration continued with the help of a £25m Lottery Grant – the biggest single grant ever given, with final completion of the project eventually taking place in 2003 when Prince Charles attended to help celebrate the event.

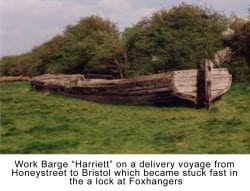

Harriett, a 72ft x 14ft Kennet barge built by Robbins Lane and Pinnegar of Honey Street in 1905 stuck fast in a lock at Foxhangers on her delivery voyage to Bristol Docks! Eventually released, “Harriett” worked on the tidal Avon and Kennet and Avon Canal, for Fred Ashmead & Sons who had her carry timber pulp. “Harriett” beached at Purton in 1964 where she can be seen today, registered as a National Historic Ship No 2347 and sponsored by descendants of the Ashmead family.

Harriett, a 72ft x 14ft Kennet barge built by Robbins Lane and Pinnegar of Honey Street in 1905 stuck fast in a lock at Foxhangers on her delivery voyage to Bristol Docks! Eventually released, “Harriett” worked on the tidal Avon and Kennet and Avon Canal, for Fred Ashmead & Sons who had her carry timber pulp. “Harriett” beached at Purton in 1964 where she can be seen today, registered as a National Historic Ship No 2347 and sponsored by descendants of the Ashmead family.

Since 1954, three generations of the Fletcher family have lived and run Lower Foxhangers Farm; diversifying into camping and farmhouse holidays since 1974 and canal boat hire since 1997.

Today Foxhangers Wharf still shows remnants of the way life used to be, having been along the route of the old Wilts Somerset and Weymouth Railway Branch Line between Holt and Patney and Chirton. The broad gauge railway was closed as part of the Beeching Axe during 1963.

Today, the Kennet and Avon Canal plays an important role in tourism and leisure as well as being a valuable asset to wildlife and conservation.

More can be learnt of the history of the canal by visiting the Kennet and Avon Canal Trust who have a Museum at the Wharf in Devizes.

Planning the Canal

Planning the Canal – The Need

Historically, the Kennet and Avon Canal comprises three waterways, the Avon Navigation from Bristol to Bath (opened in 1727), the man-made canal section from Bath to Newbury (opened in 1810), and the Kennet Navigation from Newbury to Reading (opened in 1723).

Hazardous Sea Route

The sea route between Bristol and London was hazardous during the 18th and early 19th centuries, not only because Atlantic storms and the rugged coast line took their toll on the small coastal sailing ships of the day, but also because a succession of conflicts with France and her allies, frequently made British cargo ships navigating the English channel, the prey of both privateers and warships of the French navy.

Transport by road

As transporting large volumes of goods by road was not viable at the time, both entrepreneurs and traders alike dreamt of a day when Bristol and London could be linked by a safer yet still viable alternative to the hazardous sea route they were of necessity forced to use when transporting their goods.

Avon Navigation

The river Avon had been navigable from Bristol to Bath during the early years of the 13th century but construction of mills on the river forced its closure.

Eventually a 1712 Parliamentary Bill enabled the Bristol to Bath section of the Avon to be made navigable again, although it wasn’t until 1727 that the river fully reopened to barge traffic.

Kennet Navigation

Irrespective of this, the enormity of the task meant that progress was slow and it wasn’t until 1715 that the Kennet Navigation Bill authorised the making of the river Kennet navigable from Reading on the River Thames to Newbury.

This work was completed by 1723.

Western Canal Project

In the late 1780’s canal mania swept Britain, and on 16th April 1788 a meeting of interested parties at the town of Hungerford, under the chairmanship of Charles Dundas the MP for Berkshire, concluded that a junction between the Kennet and Avon rivers would be of material benefit.

As a consequence the then named Western Canal Project was born, with the election of a committee and proposals for a survey.

Alternative Routes

Delays – Three engineers, Messrs Barnes, Simcock and Weston, were contracted to carry out survey work, and proposed a route via Hungerford, Marlborough, Lacock, Melksham and Bradford on Avon, reporting an adequate supply of water.There was no lack of support for the project although a second survey was considered necessary and in 1791 engineer John Rennie was asked to carry this out.Reporting directly to the committee, Rennie agreed with the earlier findings, although it was agreed that actual construction would not commence until £75,000 had been raised.

Delays – Three engineers, Messrs Barnes, Simcock and Weston, were contracted to carry out survey work, and proposed a route via Hungerford, Marlborough, Lacock, Melksham and Bradford on Avon, reporting an adequate supply of water.There was no lack of support for the project although a second survey was considered necessary and in 1791 engineer John Rennie was asked to carry this out.Reporting directly to the committee, Rennie agreed with the earlier findings, although it was agreed that actual construction would not commence until £75,000 had been raised.

Two further years were to pass before a group of Bristol businessmen, having become impatient with the prevarication of the canal committee organised a secret meeting at the Red Lion public house in Bristol with the intention of taking over management of the canal project.

The canal committee claimed that in two years they had been unable to raise the required £75,000, yet this group of rebellious Bristolians managed to raise £264,000 in share subscriptions at their single meeting.

The outcome was that Charles Dundas moved swiftly to accommodate the new interest, an equitable division of shares was agreed, and the project was able to progress.

Lack of water supply

John Rennie was commissioned to carry out a third survey, reporting back through Robert Whitworth the committee’s engineer.

This time Rennie found that there was in fact insufficient water available on the original Marlborough route and recommended that the canal should be built via Devizes. It is likely however that it was not only the lack of water that prompted this decision, and in his 1839 book Chronicles of the Devizes, Waylen states that the new route was in fact agreed as a result of lobbying by two Devizes MPs.

Whilst Devizes gained economically from this decision, Marlborough did not, and as plans for a branch canal to Marlborough had also fallen through, the people of that town felt very hard done by.

They were ultimately placated however by an offer of reduced carriage tolls for goods dispatched to Marlborough.

Royal Assent

The Kennet and Avon Canal Act received Royal Assent on April 17th 1794 and Rennie was appointed consulting engineer.

Summit route altered

An independent assessment of the proposals, however, was sought from another engineer William Jessop who, in a report later that year, largely agreed with Rennie’s proposals but suggested a number of small route changes. The most important of these was a recommendation that the summit route should be moved slightly to the north. This avoided the need for a tunnel of more than two miles in length with a saving in both construction time and money. It did, however, require water to be pumped to a much shorter summit pound necessitating 6 extra locks of eight feet rise each, and a length of deep cutting.

The arrangements subsequently implemented to allow this to happen, resulted in the creation of Crofton pumping station and the reservoir at Wilton Water.

However Lord Bruce the local landowner was having nothing to do with a deep cutting through his land, and insisted on a tunnel instead.

As a consequence a costly 502-yard construction had to be built, and this became known as the Bruce Tunnel.

Building the Canal

Building the Canal – Canal Technology

Methods

The methods and equipment used to construct canals in 1794 were relatively basic, and although steam powered equipment could sometimes be used, in the main picks and shovels were used for digging and wooden wheelbarrows for moving earth and rocks.

Clay lined the channel to make it watertight, and brick and stone was used to build structures such as bridges and locks.

Timber was the material for creating lock gates and swing bridges, and both cast and wrought iron for constructing pumps, ornamental bridges and various other metal components that were used in the construction process. At this period metallurgy was still in its infancy and the production of steel was as yet not possible

Innovation

It was however a period of rapid change and innovation, and canal engineers were at the forefront of this. Where this was concerned, John Rennie for example, is credited with being the first man to use cast iron ball races to enable swing bridges to pivot more easily.

Steam-powered pump

Steam operated beam engines were utilised for powering pumps and two engines ofthis type were installed at Crofton, near Great Bedwyn, Wiltshire.

A reservoir had been created at Wilton Water by damming a number of small streams, and the Crofton pumps took water from there and pumped it to the summit pound.

A good supply of water was necessary at the summit point of all canals so that an initial water supply was available in both directions.

Water-powered pump

Another form of pump, this time powered by a water wheel operating in the River Avon, was used at Claverton to pump water from the river to the nine-mile pound heading east between Bath and Bradford on Avon

Locks

Changes in level on the Kennet and Avon were achieved by the use of pound locks.

These consist of a chamber on the line of the canal which is closed at each end by mitred gates and has a facility for filling and emptying the chamber by means of sluices (paddles).

Boats that enter this chamber are thus raised or lowered as water is let in or drained out of the chamber.

Where steam or other mechanical arrangements could not be utilised, and in particular for hauling boats and barges, the horse was the motive power.

The ‘navvies’

The canal company and its contractors also employed labourers who were known as navigators or navvies (hence the term in use today).

These men were usually agricultural labourers who found canal building work more financially rewarding than that associated with farming.

During the boom years some workers would follow the canal contracts, providing a ready pool of labour for the company to use.

Contemporary newspaper reports of court proceedings at places such as Bath, Devizes, Salisbury and Newbury, suggest that drunkenness and rowdiness amongst the navvies was a common occurrence, and one which caused much concern within the rural canal side communities.

Poor Administration

The administrative organisation established to control canal building was far from ideal.

In particular the financial responsibility delegated to district committees was unfortunately accompanied by a lack of inspection of completed work.

This invariably resulted in work having to be redone, and corrupt practices such as payment for uncompleted work, false completion statements, and even payment for work that had never been started, created many problems.

The perpetrators did not however always get away with their offences and in 1798 for example the canal company prosecuted James Hollingworth of Seend, Wiltshire, who had been paid £2,397 for £1,668 worth of work.

Unable to account for the discrepancy, and unable to make repayment he was sent to prison for the debt.

These problems aside, the canal building gradually progressed mile by mile and lock by lock, and the completion of each section opened up yet another length of waterway for trade and communication.

Building the Canal – The Engineers

Need for new skills

During this period canal building was in its infancy, and although the engineers involved had experience in designing and building water wheel powered mills, the technical requirements of canal building was such that they had to develop new skills, equipment, and approaches.

These included surveying methods and skills, as well as map making, which was largely learnt from military engineers who, up to the late 18th century, were the only professionals involved in such work.

Water management

Canal engineers also had to develop new ways of water management, often involving the building of pound locks, creating new or diverting existing watercourses, and pumping water to where it was required.

These men were innovators developing new solutions to hitherto unknown problems such as building skew bridges at an angle across the canal.

Problem definition and associated solutions were initially empirical in nature, but later better-educated engineers such as John Rennie were able to use more analytical approaches.

Building the Canal – The Builders

Building committees

The building of the Kennet and Avon Canal was initially the responsibility of three district committees; the Western District, the Wiltshire District and the Eastern District.

In 1802 the Wiltshire District was subsumed into the Western District.

These committees had delegated financial responsibility and awarded contracts for construction and other associated work.

Most of this work was awarded to local businesses and, in addition to constructing the canal itself, these businesses were contracted to build associated roads, bridges, workshops, and houses.

Demand for stone

During this period the requirement for stone became so great, that the canal company opened its own quarries near Bath.

Stonemasons

Local men were employed in the quarries and as stonemasons. Careful examination of bridges and other structures on the canal reveal what are known as ‘masons marks’.

These marks were carved by individual stonemasons and, have the appearance of Egyptian hieroglyphics.

In practice the marks were used to show supervisors which mason was responsible for a particular run of work over a known period.

This arrangement provided an early form of quality control, as well as allowing piecework assessments to be made prior to payment.

Working Boats & Barges

Building the Canal – Building Methods, their problems & Solutions

Surveyors

John Rennie and the committee of management appointed different surveyors at various times to survey the possible and chosen routes.Each surveyor did this either on foot or on horseback, making measurements and calculations for every mile travelled. At its western end the building route passed through hilly country and the only way the canal could be constructed at this point was to use the same contour level either side of the river Avon, and build aqueducts which twice carried the canal across the river valley from one side to the other. This pioneering work established a base line from which the later railway builders could further develop arrangements for constructing similar structures.

Cutting the channel

Picks and shovels together with wheelbarrows for removing waste, were the main tools for digging the channel.

However in deep cuttings, arrangements for dragging men with their barrows up the sides of the cut using horse-powered winches were developed. Railway builders subsequently used these later methods when the railway system was being constructed.

Tunnels

Tunnels posed particular problems that frequently elicited simple but effective solutions.

The route of a tunnel for example, would be surveyed across the top of the ground and at fixed points the rise would be calculated from the measured elevation. Sinking shafts at these points to a depth of the calculated rise, would then produce a level for the tunnellers. Direction for the tunneling work would be taken from plumb lines lowered into the shafts, and these vertical lines would be positioned at the surface to correspond with the surveyed direction.

The plumb lines thus gave the direction at the bottom of the shaft and the result would be a straight tunnel in the right direction.

Avoiding water loss

To minimise water loss the canal channel was lined with clay, usually to a depth of 3 feet (approximately 1 metre).

The hard, quarried clay was broken into lumps, spread in the channel and wetted. Cattle would then be driven over the clay so that it was “puddled” into a malleable consistency, which allowed it to be more readily used.

Aqueducts and bridges

In addition to aqueducts, 111 bridges were built, mostly of stone at the western end and of brick, east of Devizes where locally quarried stone was less plentiful or suitable. Where aqueduct building in particular was concerned some vested interests had to be accommodated.

The original plan was to build the two Avon valley aqueducts of brick.

However the united voice of canal company shareholders who also had interests in stone quarries, forced John Rennie to build these structures of stone. Whilst the large aqueducts were major engineering projects, the smaller bridges that allowed access over the canal, were simpler to build.

These were often constructed on a timber frame that was removed after completion of the building work.

Keeping a level course

Early canals followed a single contour as much as possible to reduce the number of locks but this led to some strange meandering routes. By the time that the Kennet and Avon Canal was built a “cut and fill” technique had become the accepted method for maintaining a level. Using this technique a cutting would be made through high ground and the spoil used to build an embankment across lower lying terrain. In practice though the canal builders needed to be flexible, and former methods were sometimes still used if considered appropriate at the time.

Working the Canal – The Boats & Barges

Types of craft

Narrow boats and Kennet barges were the primary craft used on the Kennet and Avon Canal.The canal company specified that these had to be of the following dimensions:

• Approved barge (Class A) – 69 feet (21m) long x 5 feet

(1.5m) deep x 12ft 4ins (3.8m) beam, with a capacity of

60 tons.

• Approved boat (Class A) – 69 feet long x 4 feet (1.2m)

deep x 6 ft 11ins (2.1m)beam with a capacity of 35 tons.

• Non – approved vessels (Class B) – to the maximum

dimensions of 69 feet long x 5 feet deep x 14 feet (4.3m)

beam, with a capacity of 70 tons.

The company also approved a boat it called the mule boat (wide boat).This had the same dimensions as the approved barge except that the beam was 10 feet (3m) giving it a capacity of approximately 50 tons.

While the cabin of the barge was below the rear deck with access by a companionway, the mule by comparison had the appearance of an over wide narrow boat.

Larger boats

These criteria aside, larger barges were sometimes built, particularly for use on the Avon Navigation. One such vessel was the ‘Harriett’ which was built in 1894 by Robbins Lane and Pinniger, for Ashmeads of Bristol.This barge was over 70 foot long with a beam that was slightly over 14 feet.

On her delivery voyage from Honeystreet to Bristol, ‘Harriett’ stuck fast in a lock at Foxhangers near Devizes.

In order to continue their passage, the delivery crew chipped away portions of the wooden quoins and brickwork in the lock sides causing a great deal of damage.

Surprisingly, the canal company took no action against Robbins Lane and Pinniger for the damage caused, simply letting them off with a caution. It is likely that this was because the firm had grounds for complaint against the canal company on another matter and, that some tit-for-tat private resolution was reached as a consequence.

Boat building

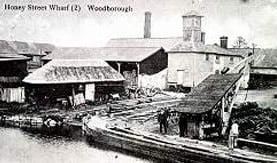

Narrow boats and barges were built in their greatest numbers at Newbury in Berkshire and Honeystreet in Wiltshire.

Robbins Lane and Pinniger of Honeystreet also built spoon dredgers for K&A use, sailing trows for the river Severn and large barges for use on the river Wey. The last trading vessel built by the company, was the barge ‘Unity’, which was built in 1896 and which continued in use until 1933. Some of the companies most well known barges were built in the early 20th century for the United Alkali Company (later ICI). These were all named after precious stones and collectively known as the stone barges.

Steam dredging

Steam dredgers for use on the canal, were built by Stothert and Pitt at Bath.

These were commissioned by the Great Western Railway (GWR) who, by that time, owned the canal.

Remains of ‘Harriett’

Although a number of working narrow boats still remain, all the Kennet barges have long disappeared. That is apart from one, because the remains of ‘Harriett’ can still be seen on the banks of the river Severn at Purton, where in the mid 1960’s she was taken to be hulked, and is now named as a scheduled monument.

Although ravaged by neglect and the elements, the shape and form of the old barge is still very evident and many of her oak timbers are as solid as the day they were fitted nearly 110 years ago.

Using the Canal

Using & Working the Canal – The Communities

Regular services

By the time work on the Kennet and Avon Canal was completed, both the Kennet and the Avon Navigations had long histories of use, and trade had continued on these waterways for many years.

By the time work on the Kennet and Avon Canal was completed, both the Kennet and the Avon Navigations had long histories of use, and trade had continued on these waterways for many years.

It therefore followed that as the new waterway gradually reached completion, the knowledge, skills, working practices and social arrangements associated with the original navigations, spread to significantly influence the canal and its operational environment.

Once the canal was operational, long distance trade between London, Bristol, and the inland towns between, soon developed.

Families

Regular services were provided by some carriers from Bristol to major London wharves such as those at Queenhithe Dock, Kennet Wharf, and Three Cranes Wharf, all close to Southwark Bridge.

Apart from these regular services, there were additional special transport contracts.

For example in 1812 the marble plinths for Lord Pembroke’s new colonnade at Wilton House near Salisbury were delivered by barge from London to Devizes.

Compared with travel by road, the regular canal service was considered to be exceedingly fast, with duplicate crews working all day and through the night, and regular changes of horses being arranged at suitable locations along the canal. Eventually these arrangements enabled a five-day delivery service between the two cities to be established.

A vast improvement on the long, dangerous, and uncertain travel a coastal voyage would entail.

Skills

The elder Hams, Tom’s father, earned 12 shillings (60p) a week as master of the Kennet Barge Unity.

This amount was below the national average for barge work at the time, but if a barge master did not have to pay for his crew or stabling for the horse, and had housing provided, then it could well have been a reasonable income.

Honeystreet was an important trading point on the K&A with virtually the whole village owned by Robbins Lane and Pinniger, who provided housing for their workers.

This sort of arrangement was not uncommon at the time, and with such stability it is not surprising that little migration occurred, and that rural families often remained in one area for many generations.

Crews

Many of the boats used were individually owned, with the owner and his immediate family living aboard in what was likely to be their only accommodation.

This arrangement enabled family members, including children, to undertake crewing duties, and as the work was invariably unpaid, costs could be kept down and hopefully, profits and income for the family increased.

Earnings

In 1844 the canal company ruled that each barge or pair of boats working “fly” (fast service with navigational priority) must be crewed by a captain and four men and that each single boat had to be crewed by a master and three men.

In 1844 the canal company ruled that each barge or pair of boats working “fly” (fast service with navigational priority) must be crewed by a captain and four men and that each single boat had to be crewed by a master and three men.

Museum records show that Tom Hams and his father, George, both worked as bargemen for Robins, Lane and Pinniger, a local company established in 1812 as boat builders, traders and sawmill owners at Honeystreet in Wiltshire.

Trades

In addition to barge and boat owners and their families, canal operations required many other trades and skills for its successful operation.

These included maintenance and other engineers, boat builders, carpenters, blacksmiths, toll clerks and agents, as well as wharfingers, masons, lock keepers, and labourers.

As an example of this, the canal company employed the following staff in 1823.

Some of these were provided with the remuneration shown:

• One engineer – £300 pa plus house

• One sub engineer & mason – £100 pa

• Thirty-one lock keepers – 10/6 (52 ½ p) per week plus house

• Twenty-six navigators

• Twelve carpenters

• Two pump men

• One blacksmith

Using & Working the Canal – The Cargoes

Local trade

Whilst the canal had been built primarily to link the ports of Bristol and London, a proportion of the trade was more local.

Whilst the canal had been built primarily to link the ports of Bristol and London, a proportion of the trade was more local.

Tolls

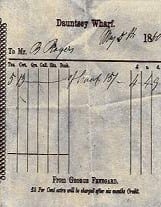

The Company charged tolls on goods carried at so many pence per mile and for this purpose goods were divided into 4 classes, each carrying a different charge.

This list (right) indicates the diversity of cargoes carried.

In order to properly administer the toll system, the company arranged for all canal craft carrying cargoes to be gauged at special docks. This procedure involved measuring the freeboard, or dry inches, with a toll staff. Weights were added to the boat in ¼ ton or ½ ton stages. In this way a toll collector could determine the weight carried by a narrow boat or barge of any size and capacity.

Tributary canals

At approximately the same time as the Kennet and Avon Canal became operational, the Somerset Coal Canal and the Wilts and Berks Canal were also completed.

At approximately the same time as the Kennet and Avon Canal became operational, the Somerset Coal Canal and the Wilts and Berks Canal were also completed.

Coal from the Somerset coalfields was brought down the coal canal to join the K&A at Brassknocker Basin at the western end of the Dundas Aqueduct.

From this junction coal could be taken anywhere on the Kennet and Avon, and soon became an important cargo.

The Wilts and Berks Canal ran from Semington, near Melksham, Wiltshire, to the Thames at Abingdon, Oxfordshire, and was used as a short cut for trade between the Midlands and the western end of the K&A. These tributary canals whilst being important in their own right, also provided an added advantage in that they allowed an increase in markets for the products of those traders that used the K&A.

Cargoes

Whilst cargoes were often diverse in nature, George Hams spent much of his working life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries carrying tin plate boxes from Robbins Lane & Pinniger to Bristol, on the barge ‘Unity’, returning from Avonmouth near Bristol with deal boards and scantlings.A trip to Avonmouth or to London with a horse drawn barge was not an easy journey.The canal company which, by then, was the GWR, did not allow steam powered vessels to trade on the waterway as they claimed that such craft caused bank wash and increased the cost of maintenance as more frequent dredging became necessary as a result. As a consequence horse, or some times manpower, was the only motive force available, particularly as sails were normally impracticable within the confines of a canal.

Alec Huntly who lived beside the canal at Honeystreet remembered seeing timber stamped with exotic sounding names such as Archangel, Murmansk, Bergen and Oslo being delivered to Robbins Lane and Pinnegar’s wharves.

That company also ran a fertiliser factory at Honeystreet, near Pewsey in Wiltshire and Tom Hams, who worked as a bargeman at Honeystreet, for example, used to take the barge Unity to Avonmouth to pick up carboys of acid using two horses to haul the laden barge back up the Avon and on to Honeystreet.This journey was made necessary because the canal owners (GWR) considered the cargo too hazardous to transport by rail.

Only one horse was needed to return the empty carboys, so two days after the barge departed from Honeystreet the second horse, which was needed for the long haul back, would be walked to the station at Woodborough, near Pewsey to catch the train for Bristol and so meet up with the barge again.

Wharves and Ancillary Trades

Wharves

Many more wharves existed in the 19th century than are in evidence today.

Many more wharves existed in the 19th century than are in evidence today.

At Newbury two whole canal basins now lie beneath the library and car park.

At Reading the entire length of the river was lined with wharves.

Although today, only one wharf can be seen at the Wiltshire market town of Devizes, where there were once seven.

Approaching Devizes by canal from the west, one first encounters Marsh Lane Basin at the bottom of Caen Hill. Most of the western edge of this triangle of water was wharf with a basin in the north corner. The main trade here was in road materials and manure.

Above Caen Hill there was a dock where St Peter’s Church now stands.

The Quaker meeting house now occupies what was Sussex Wharf, and old stables are still located on Lower Wharf, behind Wadworth’s brewery.

After this comes Town Wharf, which is the only one remaining today and just before the canal bends sharply is what was once a stone wharf at London Road.

Finally there was a sand wharf near Coate Bridge from where very fine sand that was used in foundry casting, was transported to Bath and Bristol.

Technical and economic change including the loss of trade to railways and road transport resulted in a gradual run down and the closure of many of the once busy wharves all along the waterway.

Ancillary Trades

In its heyday the canal brought prosperity to the areas through which it passed, changing small rural villages such as for example Pewsey in Wiltshire, into relatively prosperous towns.

In its heyday the canal brought prosperity to the areas through which it passed, changing small rural villages such as for example Pewsey in Wiltshire, into relatively prosperous towns.

Not only did the canal provide an effective means for the transport of a myriad of goods, but it also enabled a number of ancillary trades and activities to flourish.

Waggoners

Some of the most prominent of these were the waggoners, who provided an essential service delivering goods to and from the wharves, and the wheelwrights who manufactured and repaired wheels for the carts and other vehicles that carried those goods.

Wheelwrights

At Great Bedwyn there was a wheelwright’s shed on the wharf, and the last wheelwright operating from there ceased to trade in the 1940s.

Blacksmiths

Other associated trades included blacksmiths who not only produced much of the ironwork used on the canal but also provided the regular function of shoeing horses.

Stabling for horses

Horses also needed stabling and some of the original stable buildings are still in evidence along the canal, although most are now used for other purposes.

Boat building

Boat building was also an important ancillary trade, and in addition to large boat building concerns such as Robins, Lane and Pinniger at Honeystreet, it is likely that some craft were simply built on the side of the canal in a position where they could be easily launched side on.

Timber trade

Boats and barges for use on the K&A were mainly built using local timber from the Savernake Forest and from around the town of Hungerford. Timber was labouriously reduced by sawing over sawpits, and knees and other acutely bent timbers were fashioned from branches which had naturally grown to the shape required. The heavy oak timbers used for planks, were bent where required by steaming until supple enough to be forced into place around the boat or barges frames. All this work was carried out with a minimum of tools and required great skill in application.

Plenty and Sons

Other local firms whose products supported the canal trade were Plenty and Sons of Newbury, who produced steam engines for pumping and other applications, and various sail and rope makers from whom canvas tarpaulins and sheeting to protect cargoes, and ropes for a myriad of uses, were purchased.

Acramans Cranes

Crane makers such as Acramans of Bristol also provided essential equipment, and installed their products on wharves along the canal. The one remaining Acramans crane can still be seen at Dundas Wharf at Brassknocker Basin where it has stood since around 1830.

The Decline of the Canal

For thirty years traffic on the canal grew and grew, with annual receipts between 1824 and 1839 for example in excess of £42,000 with a dividend of 3%.

Railway competition

However as soon as the Great Western Railway started operating from London to Bristol in 1841, the competition started affecting canal trade. Ironically much of the canal company’s profit in the late 1830’s, came from transporting those self same materials that were used to build the railway.

Fighting back

For the next ten years the canal company fought back against railway competition by reducing tolls and introducing its own fleet of barges.

New services

Increasing fly-boat services and extending passenger carrying facilities were other methods of remaining competitive that were tried.

Losing out to the GWR

Later as matters got worse there were staff cuts and wage reductions, and canal traders increasingly turned to the railway, viewing it as a more economical means of transporting their goods.

Railway Take-over and Operation

In 1852, the GWR obtained Parliamentary approval to take over the whole canal.

The canal company shareholders were guaranteed an annual payment, and the GWR promised to keep the canal in good repair and try to run it in a business like way.

However as profits gradually disappeared, they too began to cut staff and reduce repairs.

Toll charges

By 1906 tolls on the K&A were higher than those on similar waterways.

By 1914 railway competition had closed both the Somerset Coal Canal and The Wilts and Berks.

By 1920 some trading still existed on the K&A, although tolls had by then been raised by 150%.

Maintaining the canal

Obligations in the Act, together with local opposition prevented the canal being closed in 1926 and in 1929, the last major canal trader forced the GWR to honour its maintenance obligations, although trade was not encouraged.

Obligations in the Act, together with local opposition prevented the canal being closed in 1926 and in 1929, the last major canal trader forced the GWR to honour its maintenance obligations, although trade was not encouraged.

The Kennet and Avon during World War Two

During the Second World War, the K&A was used as a second line of defence against possible invasion.

Pill boxes were strategically sited along the whole length of the canal, and concrete obstructions placed across canal bridges. Much of the material used for these structures was carried on canal boats.

Canal Abandonment

During the years 1945 to 1948, the canal suffered even further decline due to a lack of maintenance and use although a number of smaller traders still used the waterway.

New management

As a consequence of railway nationalisation in 1948, the K&A came under the management of the Railway Executive and later under the Docks and Inland Waterways Executive (DIWE).

For a short while there was an upsurge in canal trading, when a number of enterprising businessmen found cargoes to carry.

Closure

However from the early 1950’s the DIWE effected a number of closures for repairs, and this made trading more and more difficult. These repairs were never satisfactorily carried out, and in 1955 the Transport Commission went to Parliament to close the canal. A few years later and after considerable campaigning, the restoration of the Kennet and Avon Canal was started and the Kennet and Avon Canal Trust formed. After several decades of fundraising and hard work, the Kennet and Avon was eventually re-opened by Her Majesty The Queen in August 1990.